- What Active Listening is and Why You Should Learn to Do It

- The Basics of Active Listening

- How to Become a Skilled and Effective Listener

- Fine-tuning your Active Listening

What is Active Listening

As children go through their day, they experience many moments of exhilaration and frustration. Often the quality of your day can feel tied to your children’s roller-coaster of emotions. One way that you can keep yourself on an even ride is to learn how to steady their ups-and-downs.

Listening to your children is the chief skill you can use. You can hear their disappointment when they do not make the team; you can accept their frustration when their plans do not work out; and you can acknowledge their dissatisfaction when they complain that their friends have more freedoms than they do.

It can feel like a relief to learn that you do not need to “fix” everything for your children.

-

By listening to them, you are communicating that they are worthy of your attention.

-

By hearing their distress, you are demonstrating that their view of the world has merit.

-

By allowing them time to decide their course of action, you are indicating your trust in their ability to solve problems.

Active Listening is the single most important skill you can have in your parenting “toolbelt.” It is a specific form of communication that lets another person know that you are “with them,” aware of what they are saying, accepting of their perspective, and appreciative of their situation.

Really listening to your children is the best way to create a caring relationship in which they see you as being “in their corner” and as a base to which they can always return when they need support.

Having this secure relationship is one of the strongest factors in helping your children to become resilient, responsible, and caring people who are open to your love and your guidance.

Acceptance is key

When you are active listening, there is no judgment or evaluation of what the speaker is saying. Often parents resist at this point, thinking that Active Listening implies that you are agreeing with whatever your children are saying.

But accepting is not the same as agreeing.

For example, your child may declare angrily, “I was the only one in the class not invited to the party.” While you may know this statement to be untrue, you can accept that your child feels left out by saying, “You are upset that you weren’t included.”

Had you countered your child’s statement with “I know Joshua wasn’t invited,” you may have gotten into an argument over Joshua’s social status. By accepting your child’s view, you free him up to focus on his own feelings, perhaps even clarifying his own thoughts. “She only invited the ‘cool’ kids.”

Acceptance is the heart and soul of Active Listening. It is not the time to object, teach, help your children to solve a problem, or ask a ton of questions. This is a time to let your children talk without interruptions or judgment, while you listen to what they have to say.

Practice makes perfect

Active listening is a very sophisticated skill that can take years to master.

Active listening is a very sophisticated skill that can take years to master.

Because you may not have been raised in a home in which this kind of listening was practiced and because very little of it occurs in our fast-paced, solution-oriented society, it can feel like you are learning a second language.

It is no wonder that when you first begin to practice this skill, it can feel forced, unnatural, and uncomfortable.

Examples

To get a feel for Active Listening, read the following three scenarios which show how three different parents could respond to the same situation that their 10-year-old daughter wants to discuss.

As you read, please think about how the parent and the child are feeling and how the parent’s responses affect the relationship between them.

Scenario 1:

Daughter: (sounding glum) I don’t want to go to school today. It’s boring.

Mother: (said roughly) Of course you want to go to school today. You have Physical Education today and you always love that.

Daughter: No I don’t. Besides we’re playing basketball and I hate that.

Mother: Well, you better learn to like it, and to like school too. You don’t have a choice, you know. You have to go to school. Everyone has to do things they don’t want to do and you are no different.

Daughter: (Slinks away, dejected with shoulders and head hanging down, whimpering) I hate school and I hate gym.

This parent seemed annoyed, angry, and impatient, and didn’t want to hear that the child hated school. The child felt that her mother wasn’t listening to her and would eventually learn not to turn to this mother for support.

Scenario 2:

Daughter: (sounding glum) I don’t want to go to school today. It’s boring.

Mother: (sugary) Oh, that’s awful. School shouldn’t be boring. You are so bright, you need a lot of exciting things going on to keep your interest.

Daughter: Well, I hate school and I don’t want to go.

Mother: I’m going to just go right up to school and tell Mrs. Tanner that she has to make up special lessons that will keep you interested.

Daughter: No, Mom, don’t do that! I’ll be fine in school. I’m going to do my homework now. Please don’t talk to Mrs. Tanner.

This mother jumped right in with praise for her daughter and a solution to the problem. She seemed unable to tolerate that her daughter might be unhappy. The child didn’t want her mother’s intervention and decided she was better off not talking to her.

This daughter probably will not continue to turn to her mother if she is unhappy in the future.

Scenario 3:

Daughter: (sounding glum) I don’t want to go to school today. It’s boring.

Mother: You’re not happy at school because it isn’t interesting to you.

Daughter: Yeah. Nobody likes it. And the kids don’t listen to the teacher when she tells them to do something.

Mother: It bothers you that the other kids don’t behave.

Daughter: They are mean to me and some other kids – when the teacher isn’t looking, they throw rolled up pieces of paper at me. I hate that. And Mrs. Tanner doesn’t even know what’s going on. She is so lame.

Mother: You’re really angry at the kids and feel so let down that your teacher doesn’t even do anything about it. You would expect the teacher to know what is happening in the room.

Daughter: Yeah. I want to let her know what the other kids are doing.

This mother did not get angry and she didn’t jump in with solutions. Here’s what she did that helped her daughter deal with the situation:

-

She listened without judging.

-

She tuned in to what the daughter was saying and feeling.

-

She kept herself separate from the situation her daughter was describing.

-

She was able to tolerate the daughter’s sad, angry, and disappointed feelings.

As a result, the child was able to talk about the situation in the classroom in more detail, and the mother found out what was really bothering her daughter.

This last scenario is an example of how Active Listening can help empower your child by aiding her in getting clear about what her feelings are and even in coming to some decisions on her own about how she wants to handle a situation. Ultimately it brings this parent and child closer together.

The Basics of Active Listening

Why is Active Listening Difficult?

There are certain attitudes you need when you actively listen to your children, and as a parent, these are sometimes hard to summon.

sometimes hard to summon.

-

You may have your own agendas for how you want their situations resolved.

-

You may feel uncomfortable when your children are experiencing something unpleasant.

-

You may not like when they have certain negative or painful feelings.

-

You may have a hard time separating your feelings from theirs.

Necessary Attitudes

With time being a valuable commodity in your busy life, easy and quick solutions may be desirable, and taking the time to listen may seem like an inconvenient chore. But it is important to strive to achieve the following attitudes:

-

Accept the feelings and perceptions of your child.

They are real for him, even if you do not agree with them. -

Be objective and keep your feelings separate from your child’s.

Use your knowledge about your child to intuit what his feelings might be. -

Allow your child to be responsible for his own feelings.

Stay separate from his experience. -

Have the necessary time.

When you can, stop what you are doing to give your child your full attention when he needs to talk to you. -

Recognize that feelings are often transitory.

Often, once a child is able to vent his feelings, they lose their intensity and he is able to move on quickly. It is said that positive feelings cannot come through until negative feelings come out. After that, your child will be more able to focus on solutions. -

Let the exchange go only as far as your child wants it to.

Don’t push him to continue to talk after he seems satisfied or wants to stop. -

Allow your child to draw his own conclusions.

Be patient. -

Do not have some specific result in mind.

Often parents will say of an active listening exchange with their child, “It didn’t work,” meaning that no solution or the solution the parent had in mind was not achieved.

However, the real goal of active listening is for the speaker to feel heard and have a safe place to vent and talk, and for the relationship between the speaker and listener to be deepened.

Sometimes, there is not any way to “fix” the situation, but, just by listening, your child knows that at least one person in the world cares about him and is on his side.

Active Listening is the best parenting tool when you:

-

sense strong feelings on the part of your child.

-

think that your child needs to vent emotions, feel understood, or have an opportunity to clarify his thoughts by talking with an accepting person.

-

are not involved personally in the situation – the situation is not your problem and you can stay separate and objective.

Active Listening would NOT be appropriate when:

-

your child needs information, not someone to listen to him.

For example, if your child asks what time he has to be home for dinner, you wouldn’t respond with: “You’re wondering what time you need to be home for dinner.” Rather, you would just answer his question.

-

your child is more in need of reassurance, praise or discipline.

Obviously, if your child is about to hit his younger brother over the head with a toy truck, you would not say: “You’re really angry with Sean right now.” Rather, you would take action; you can listen to how angry your son is after you have secured Sean’s safety.

-

you feel resistance and your child does not want to talk. At times like that, you can say, “I’m here for you whenever you do want to talk.”

-

you have some investment in the outcome of the situation or any decision your child makes.

In Scenario 1 above, the mother wanted her daughter to go to school, so she was not able to hear anything beyond the daughter’s statement that she did not want to go.

-

you have strong feelings on the subject so you cannot remain objective and separate.

In Scenario 2, the mother was not able to listen to her child’s negative feelings of being bored and not liking school; she took as a personal affront that the teacher was not providing enough stimulation for her very smart daughter.

-

you are too needy yourself or feel too drained to give the time and energy needed to focus on your child. Don’t force yourself. It is better to be honest that you are too tired to give your child your full attention than to be distracted and have him misinterpret your response as a lack of caring.

For example, “I hear how angry you are with your brother. I’ve had a really long day and can’t give you my full attention right now. I need to rest and then I can listen to you about what happened.”

Remember that Active Listening to your children is one of the most important gifts you can give them. It can help you create a very special and supportive bond with them in which you both feel a heightened sense of self-esteem and closeness.

If you are non-judgmental and accepting of what is on their minds, they will feel more comfortable opening up to you and will have a trustworthy place where they can explore their reactions and feelings.

By becoming a safe haven for your children, they will see you as someone they can turn to in difficult situations, even during the teen years when they could face difficult and complicated life choices.

How Do Your Really Listen?

Listening involves paying full attention to what your children have to say.

It means turning off the running dialog that goes on in your head – the one where you are so busy thinking about all the things you need to do or should be doing or you are so busy thinking of the perfect response to your children that you miss half of what they are saying to you.

If you are too busy at the moment to listen, then you can set an appointment with your child to talk at a later time.

For example, “I need to make a few phone calls before 5:00, but after I am finished, I am all yours.”

It is important that you keep your commitment and don’t get involved in another activity. You want to communicate to your child that he is important and that you care about his thoughts, feelings, and struggles.

Five different ways to Active Listen

Non-verbal Active Listening

Non-verbal Active Listening

A non-verbal listening response involves little or no verbal activity, but you show attentiveness by nodding and making facial expressions in response to your children’s statements. Non-verbal responses also include such ‘comments’ as “I see” or “Uh hum.”

Through body language, you can convey to them that you are interested in what they have to say and are willing to take the time to listen.

When you sense that your children want to talk, you set aside what you are doing, establish eye contact or lean forward to indicate you are listening, and don’t answer the phone or look at your mobile device.

These non-verbal responses can be represented by a ticket to a movie – in which you are watching and listening and attending, but not speaking.

Content Response

A content listening response reflects back to your children the content of what you heard. This should be a paraphrase and not a parroting, which can be annoying and can sound false.

A content listening response reflects back to your children the content of what you heard. This should be a paraphrase and not a parroting, which can be annoying and can sound false.

For example, when a child says, “I can’t sleep because I think a monster is going to get me,” a content listening response would be: “When you think there is a monster who might hurt you, you can’t get to sleep.”

These Content Responses can be represented by a mirror because you are reflecting back what your children have said to you.

Feeling Response

A feeling listening response focuses on the emotions you think your children might be experiencing. Notice the word “think” – the tone for any Active Listening response is usually tentative, almost as if it ended with a question mark, as if you are checking with your children that you accurately picked up the feeling underlying the words.

A feeling listening response to the child who can’t sleep would be: “When you think a monster might get you, you are too scared to go to sleep.”

These feeling responses can be represented by a trash can, in  which your children can dump their feelings when they vent.

which your children can dump their feelings when they vent.

A caution: While it is important to allow your children to vent and share their feelings, if recounting the story over and over seems to escalate their emotions – rather than help dissipate them – you need to stop the rant.

For example, “I know how upset you are. I think you need to take some time to calm down and then we can talk some more.”

Clarifying Response

A clarifying listening response takes a much broader or deeper view of the situation your children are facing, offers other possible reactions and identifies potential needs, values, expectations, wishes, and underlying issues.

A clarifying listening response takes a much broader or deeper view of the situation your children are facing, offers other possible reactions and identifies potential needs, values, expectations, wishes, and underlying issues.

A clarifying listening response to the child worried about the monster would be: “Thinking there is a monster somewhere around makes you feel as though you have to stay awake so he can’t get you; if you fall asleep, you worry you won’t be able to protect yourself.”

Clarifying Responses can be represented by a calculator which helps someone to process information.

Universal Truth Response

When you use a universal truth listening response with your children, you are offering a broad commentary about the situation that reflects their needs, feelings, or experience. Often these responses are ways to teach your children a principle about life that relates to the situation and their reactions to it.

Such statements can give your children food for thought as far as processing the situation and can help them to feel less alone. After all, you are telling your children that others have walked in their shoes and gone before them. Making your statement in the third person makes it seem more objective.

A Universal Truth listening response to the frightened child might be: “People can be afraid even if they have been told over and over that there is nothing to be afraid of. The feelings just stay even if the person knows in his head that what he is afraid of really isn’t there.”

These responses can be represented by the world since you are giving your children universal truths which tell them that other people often react in the same way as they have to a similar situation.

Five Healthy Non-Listening Responses

There are five responses that are healthy and appropriate at certain times, but they are not active listening. As a parent, you want your children to be happy, and the hardest thing to do is listen to their struggles – you want to do something. However, your actions may get in the way.

There is definitely a time and place for the following responses; but since they are not Active Listening responses, they will not necessarily help your children to explore a situation and come to their own decisions about how to handle it. They do not allow your children to vent their feelings; in fact, they can cut off discussions.

And they do not necessarily enhance your relationship with your children in the same way that Active Listening can, encouraging closeness, respect and ultimately, independence.

Below are the common traps that parents fall into when trying to listen to their children.

Reassuring

You want to promise your children that it will all be okay in the end, it’s not such a big deal, and things will work out for the best. While their problems may seem small and easily rectified to you, they don’t seem so to your children.

By reassuring your children too quickly, you minimize the problem and stop the conversation.

You want to tell your children that they are fully capable of handling the situation. But if they are not convinced they can, your reassurance can feel like you are discounting the situation. It is as if you are saying that whatever the problem is, it is not so bad.

Examples of statements meant to reassure:

“It’s going to be all right soon, I’m sure.”

“You can do it.”

“Oh, you are such a big boy; you can handle a few extra hours of work. It will be all right.”

“It’s going to be all right soon. You’ll be fine.”

“No big deal. Forget about it. This happens to kids your age.”

After your children have had an opportunity to vent, you can certainly help them to gain perspective, encourage them to find solutions, and remind them of their ability to overcome the obstacles. However, that strategy can only be successful AFTER children have been heard.

Explaining

Because your children are still young, they may lack all of the knowledge or information needed to accurately assess a situation. You may want to fill in the gaps and explain why another person behaved the way he did.

While quite useful and important, these explanations fall under the category of teaching – an important part of parenting, but not part of listening.

This form of communication tends to place the focus on the situation, not on your children, their experiences, or their reactions. It suggests they consider things at an intellectual level rather than a feeling level.

Examples of statements meant to explain:

“The reason this might have happened is…”

“This happened because you weren’t paying attention. Next time you better watch where you are going.”

Suggesting

Again, you want your children to be happy. It is uncomfortable to watch them struggle, especially when the solutions to their problems are quite clear to you. Like teaching your children, helping your children find ways to resolve a difficult situation is an important part of parenting.

However, if you move into that mode too quickly, your children do not feel heard and usually reject any of your attempts to help.

This form of communication also moves the conversation into an action mode. It denies the importance of venting feelings, sorting them out, and processing. It may tell your children that they are not capable of handling the situation, and that you know best.

Examples of statements meant to solve:

“A way to handle this is…”

“Have you thought about trying to…?”

“Well, a way to make the time go quickly would be for you to read for 20 minutes and then help Susan build a castle and then…” “

“If you just stay near a teacher, you’ll be safe. The first thing you need to do when a fight is about to start is get away.”

If you can hold back and really listen first, then your children may become open to your ideas and suggestions.

You can test your children’s readiness by asking “Do you want to think about what you can do to resolve this situation?” Then, see if they have ideas for dealing with it on their own or if they need your assistance.

But again, they can only move to the problem solving stage after their emotions have been released and they feel they have been heard.

Sharing

Sometimes you want your children to know that you have been through the same thing that they are experiencing and that you survived. You want them to know that you understand how they feel.

Your intentions are good; however, once again, if you share too early in the process, you take the focus off your children’s experience and onto yourself. Your children won’t feel heard.

While you may be trying to say: “See how much I understand,” your sharing usually changes the direction of the conversation. It can be hard for your children to shift back to talking about themselves.

Examples of statements meant to share:

“I know just how you feel. Once that happened to me…”

“That happened to me when I was little. It made me feel terrible too.”

“When I was a little girl, I got lost once too. I didn’t think I’d ever find my way back to Grandma. I was so scared.”

Questioning

Your children come in upset and you want to understand what is happening. Frequently the story being recounted is disjointed or is told in such detail that you have difficulty understanding what the problem is. It is tempting to jump in with your own questions to clarify the situation, to speed up the process, or to get to what you believe are the important facts.

This form of communication can interrupt the process in several ways: it makes your children accountable to answer your questions; it can change the direction the conversation would have taken if your children were following their own train of thought; and it makes them move from a feeling mode to a thinking mode, from using their hearts to using their minds.

Examples of statements that ask questions:

“Why did you do that?”

“How do you feel about that?”

“How often does it happen?”

“What happened first?”

“Why didn’t you walk away?”

You can actually learn a lot just by listening to what they do include. You can discover what information they value. Do they talk about feelings or facts? Do they talk about others’ perspectives or just their own? Can they see the big picture or do they get bogged down in the details?

There is definitely an important place for each of these five responses, depending on timing, the situation, and the needs of your children. There will be times when:

-

they need reassurance,

-

when you will want to explain and teach them things so they can understand the world better,

-

when they will need you to step in to help them solve problems they are facing,

-

when you want to share parts of your life with them,

-

when you will question them in order to get more information about something they are experiencing.

But remember, when you want your children to talk, when you sense they have strong feelings, the most effective way to help them is to use the skill of Active Listening first. You can employ these other techniques later.

Fine Tuning your Active Listening

Underlying Issues

When Active Listening, it is helpful to know that at any given time or in any given situation, there are broad issues beneath the surface of your children’s words or reactions that reflect feelings, needs, or concerns. Yet they can color interactions and affect behavior even when they are not spoken, understood or realized.

These issues are universal but are expressed through different behaviors by different people at different times in their lives.

For example, when you bring a new baby home from the hospital, your three-year-old may become upset. He may be angry, he may cry,or he may regress by acting in less mature ways than he had before. The underlying issue may be jealousy, fear about being replaced, or sadness that you pay so much attention to the baby.

Over time, as he matures, these feelings may continue but your older child may be able to express them more directly with his words. As he moves more into the world, he may not feel so intensely jealous since he now has more of his own life and he may feel secure that there is enough love to go around in the family.

Recognize when an Underlying Issue is Involved

Often when children have a disproportionately intense reaction, it means that the situation has triggered feelings around some underlying issue.

Or when a reaction seems to have little or no connection to the actual situation or behavior, it may be that your children are reacting to something else, a larger and deeper issue than what is happening in the present.

Knowing this can help you manage the situation more effectively and help your children to identify the issue so that they can more appropriately manage the situation.

For example, your eight-year-old may become upset when you mention that a teenager who has taken care of your children many times in the past will be babysitting tomorrow night. Today, you may learn that the parent of a schoolmate was just in a car accident and is in the hospital; your son is actually fearful that the same could happen to you, and so he doesn’t want you to leave.

With this knowledge, you could approach your child with “You are worried that something could happen to me if I go out.” You are providing your child with an opportunity to discuss his greatest and deepest concerns.

Recognizing Underlying Issues is an important skill in Active Listening, since you can incorporate the issue into your response, giving your children an opportunity to identify what is really causing their emotions or behaviors.

Recognize your own Underlying Issues

As a parent you have your own underlying issues which effect how you respond to a situation; you may also over-react because whatever is happening in the present is triggering some underlying issue for you of which you may not be aware.

By clarifying your own issues, you can better monitor your reactions and acknowledge for yourself that you are dealing with more than just the present situation. This can diffuse the intensity of the reaction, allow you to deal more appropriately with the situation at hand, and consider your own underlying issues at another time.

For example, if you had an argument with your sister about the care of your parents, you may be impatient and irritable with your children when they ask for help. If you can keep in mind that you are preoccupied with these other concerns, you may be able to respond to your children in the present, and confront your own issues separately.

Underlying Issues Children May Face

| Competition | Rejection |

| Confidence | Sadness |

| Control (power) | Safety |

| Disappointment | Self-esteem |

| Embarrassment | Temperament |

| Fairness (justice) | Territory (ownership) |

| Fear | Trust |

| Isolation | Unmet expectations |

| Jealously | Unmet Needs |

| Loss | Vulnerability |

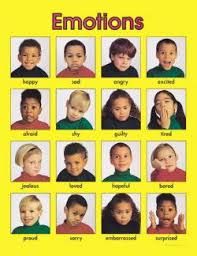

Feeling Word Vocabulary

An important way to become a more effective Active Listener is to increase your “feeling words” vocabulary. Children are not born knowing how to describe what they feel and they don’t automatically know the words to use when they do become aware of their feelings.

An important way to become a more effective Active Listener is to increase your “feeling words” vocabulary. Children are not born knowing how to describe what they feel and they don’t automatically know the words to use when they do become aware of their feelings.

You can help your children by using as many feeling words as possible when you are actively listening to them.

In doing so, you help to identify their feelings and give them words to use when they want to talk about their emotions.

Having these words readily available to you in your vocabulary can make you a more astute listener, as you may be able to better detect nuances in what your children are feeling.

Below are some feeling words you can add to your vocabulary:

| angry | annoyed | ashamed | awed |

| awkward | betrayed | blamed | burdened |

| calm | cautious | cheated | clever |

| condemned | confused | controlled | discounted |

| embarrassed | empty | energized | exasperated |

| exploited | exuberant | freed | furious |

| guilty | gullible | happy | helpless |

| hopeful | indifferent | inspired | intimidated |

| irate | irritated | joyful | powerful |

| pressured | refreshed | relieved | restless |

| settled | startled | surprised | tentative |

| thwarted | trapped | vulnerable | wise |

Feeling word continuums

To become more accurate about feeling issues, you may use continuums to help you choose the word that correctly matches your children’s feelings with the degree of intensity they are expressing.

ANGER CONTINUUM

Degrees of anger might be expressed using the following words:

Outraged … Furious… Bitter … Mad … Frustrated … Aggravated … Agitated … Annoyed

HAPPINESS CONTINUUM

Degrees of happiness might be expressed using the following words:

Ecstatic… Delighted… Thrilled… Joyous … Pleased … Contented … Satisfied

CONCERN CONTINUUM

Degrees of concern might be expressed using the following words:

Panicked… Alarmed… Anxious… Distressed… Worried … Troubled … Concerned

Sentence Starters for Active Listening

Sometimes you may not know how to begin an Active Listening response, especially when you first begin to use the skill. The following sentence starters can help you phrase your response and also help you decide about what underlying issues may be playing out for your children.

Some parents use these sentence starters as a “cheat sheet,” posting them on their refrigerator or keeping them on their night stand until they become more familiar with them:

-

“That makes you feel…”

-

“That could make a person feel…”

-

“You wish…”

-

“You would like to change…”

-

“It hurt you that …”

-

“You need permission to…”

-

“You are looking forward to…”

-

“You didn’t expect…”

-

“It bothers you that…”

-

“You aren’t sure…”

-

“You’re disappointed that . . . “

-

“You’re worried/concerned that…”

-

“You needed/need…”

-

“When you didn’t get what you needed, then…”

-

“It seems unfair that…”

-

“You can’t understand…”

-

“You think the other person is feeling/ needing/ worrying about/ trying to/ expecting…”

-

“The tension seems to be coming from…”

-

“The solution you see is to…”

-

“The confusion seems to be about…”

-

“What this seems to mean to you is…”

-

“What you think might happen because of this is…”

-

“If things could be different, you’d feel…”

In Summary

Feeling comfortable using Active Listening can take a long time; it is a sophisticated skill that requires parents to use their intuition about what their children may be feeling or what lies beneath their words and behaviors.

It is certainly not the only response to use when your children want to talk. Sometimes you may need to discipline, set limits, give reassurance or praise; other times you may want to share your own experiences and feelings, offer solutions, or help your children problem solve.

When your children are troubled or have any kind of strong emotions, some form of active listening is often the best first approach to use. After you hear more clearly what is going on with your children, you can decide what you need to do next.

Remember that to become skilled at Active Listening takes time and practice; it is well worth your effort, as everyone in your family will benefit as you begin to use this very important skill.

____________________________________________________________

For more information about actively listening, check out the following books. Purchasing from Amazon.com through our website supports the work we do to help parents do the best job they can to raise their children.

<recommended books about communication

<all our recommended parenting books

____________________________________________________________