- Part I Introduction

- Part II The Dual Role of Parenting

- Part III The Three C’s of Discipline Overview

- Part IV Staying Calm

- Part V Getting and Being Clear

- Part VI Being Confident

Part I Introduction

Have you ever faced any of these discipline dilemmas?

“How can I get my children to listen to me without having to yell and get angry? I don’t want to make them feel bad b

ut I get so frustrated.”

“When I was growing up, my parents were too strict. I don’t want to be that way but I don’t know how else I can control my children. Nothing else seems to work. But sometimes I think I am too strict.”

“My children just wear me down – I don’t want to give

in but I don’t have the time or energy to outlast them. Sometimes I feel like I am too weak and am a pushover.”

“How can I discipline my two children the same when they are so different from each other?”

“I don’t like being mean and I don’t want to be the ‘enforcer’!!!”

“What do I do if my husband and I don’t agree on how to discipline our children?”

These are som of the frequently questions and comments that parents raise regarding the issue of discipline. This part of the parenting job does not come easily to everyone, and it can feel like a huge responsibility to do it correctly. How parents handle discipline issues has a large influence on their children’s self-esteem, the quality of their relationship, and the degree to which children develop inner discipline. But often parents don’t know the best, most effective way to impose the limits that their children need.se are some frequently asked questions a

History of Discipline

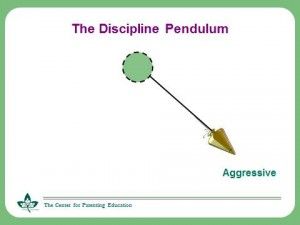

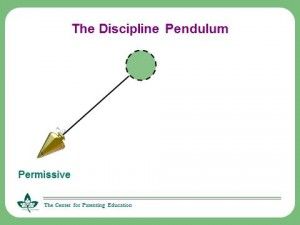

Part of the difficulty is that culturally acceptable forms of discipline in our country have changed multiple times over the past century. Until the 1950’s, the conventional wisdom fell toward the stricter end of the discipline continuum. Parents felt that children should be “seen and not heard” and that there should be no negotiation; parents should make the rules, and children should follow them without questioning. Discipline was often harsh. This is sometimes referred to as the “aggressive” style of parenting.

Beginning in the late 50’s, the pendulum swung all the way to the opposite end of the continuum, with permissiveness being the approach considered by experts to be best. Children “ruled the roost”, parents were reluctant to set limits and they were overly focused on their children’s feelings, while often neglecting their own. Homes became very “child-centered.” This is referred to as the “permissive” style of parenting.

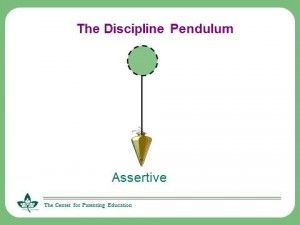

Today, the pendulum has moved to the middle range of the continuum.

Research has confirmed that the best forms of discipline:

- respect both the child and the parent.

- see both the parents’ needs and the children’s needs as important.

- maintain everyone’s self-esteem. o maintain a healthy relationship between the parent and the child.

- gradually transfer power and decision-making from the parent to the children.

Definition of Discipline:

There is often confusion about what discipline actually is. Webster’s 3rd International Dictionary defines discipline as “training that corrects molds, strengthens, or perfects.” Education is often listed as a synonym.

The word ‘discipline’ is actually derived from the Greek word for “disciple.” We can think of our children as our students and we are their teachers. A disciple follows the mentor because there is a trusting relationship between the two in which the student feels safe and believes that he is treated fairly and with respect. As a result, our children want to consider our direction as they map out their own course and eventually become self-disciplined.

Knowing that the goal of discipline is to teach your children can guide you in deciding how to react to their misbehavior. You can consider what it is that they need to learn from the situation. For example, if your four- year old daughter is hitting her younger sister when she gets angry, she may need to learn more appropriate ways to express her anger and frustration.

Discipline vs. Punishment

Sometimes people use the two words discipline and punishment interchangeably. However, there are important distinctions between them:

| DISCIPLINE | PUNISHMENT |

| Goal is to teach | Goal is to harm or hurt other person |

| Is related to the offense | Is often NOT related to the offense |

| Teaches the child the consequences of his behavior | Usually does not teach the child |

| Is consistent with the severity of the misbehavior | Is often harsh and out of proportion with the offense |

| Encourages the child to accept responsibility | Leads the child to be angry at parents and not look at his own behavior |

| Encourages the child to incorporate parents’ values | Causes the child to reject values or and limits at least be ambivalent about them |

Over time, discipline leads children to internalize rules and hold themselves accountable for their own behavior. Punishment leads children to need external controls in order to behave appropriately – if an adult is not nearby, or they think they will not get caught, children who are harshly punished are more likely to misbehave than children who have learned internal control and self-discipline.

Over the upcoming weeks, think about:

- When your child misbehaves, is your response a punishment (wanting him to feel badly) or is it discipline (wanting him to learn)?

- When your child misbehaves, decide what he or she needs to learn from the situation.

- As you discipline your child, stop and ask yourself, “What lessons am I teaching?”

Great Ideas for you to use

With awareness of these concepts, parents will be better able to incorporate healthier forms of discipline into their repertoire of responses and approaches to their children’s inevitable misbehavior. In the second of the discipline series learn specific tips, methods and attitudes that you can use to solve some of the “discipline dilemmas” that you may have.

Part II The Dual Role of Parenting

As a parent, have you ever wondered:

Am I being loving and attentive enough? OR Am I being too giving? Are my children becoming spoiled? Am I too strict? OR Am I too lenient? What is a good balance??

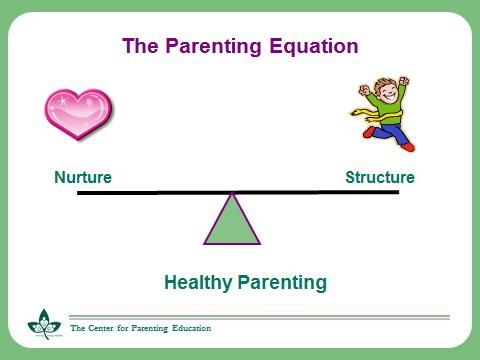

These questions point to the two broad categories into which the big job of parenting can be divided: the “nurture role” and the “structure” role. All the responsibilities of parenting fall under one of these two headings.

The Nurturing Role

In the nurturing role, parents take care of their children’s basic needs, such as: food, medical care, shelter, clothing, etc., as well as give love, attention,  understanding, acceptance, time, and support. Parents listen and are patient, and they have fun with their children. They make time for their children, show an interest in them and their activities, and encourage them in their interests. Parents communicate to their children that they are loved and accepted. Typically, no behavior changes are expected when a parent is in the nurturing role.

understanding, acceptance, time, and support. Parents listen and are patient, and they have fun with their children. They make time for their children, show an interest in them and their activities, and encourage them in their interests. Parents communicate to their children that they are loved and accepted. Typically, no behavior changes are expected when a parent is in the nurturing role.

As a result of parents being nurturing, children learn that they can trust their parents and count on them as a source of support and comfort. This helps children to feel protected and loved. Knowing that they do not have to go it alone gives them the confidence to weather problems and face challenges. By offering children empathy, parents teach children to give emotional support to other people. It is through loving and supportive early parent-child relationships that the foundations for future healthy relationships are formed. Being valued just for whom they are helps to build our children’s self-esteem.

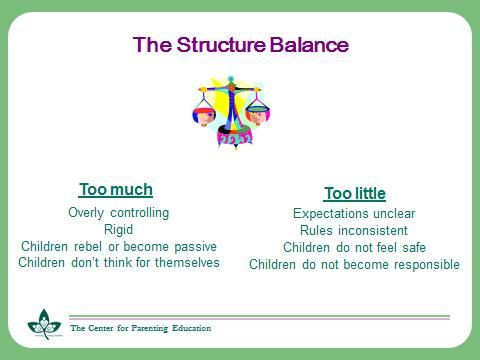

The amount of parental care and involvement needs to be weighed on a scale, as shown below. When parents give too much nurture, they may be overly protective and too involved in their children’s lives. Under these conditions, children don’t learn skills to care for themselves and they don’t learn to consider other people’s needs. Conversely, when parents aren’t nurturing enough, they are too removed emotionally and not involved in their children’s lives. As a result, children don’t feel loved or supported and they don’t learn to trust other people.

The Structure Role

In the structure or in-charge role, parents give direction, impose rules, discipline and consequences, hold children accountable and teach their values. They provide the guidance that helps children to change, grow and mature. Responsible behavior, in line with children’s maturity levels, is taught and expected.

Through this role, children learn that their parents are in-charge of their well-being. It also helps children feel secure knowing that parents will impose external controls when the  children don’t have control of their own impulses or when their judgment lapses. Children become more self-sufficient and capable as parents teach skills needed to become independent. Learning that they are capable of meeting standards and handling life’s challenges also builds self-esteem.

children don’t have control of their own impulses or when their judgment lapses. Children become more self-sufficient and capable as parents teach skills needed to become independent. Learning that they are capable of meeting standards and handling life’s challenges also builds self-esteem.

Just like with the Nurturing Role, the Structure Role exists on a scale as shown below. When parents provide too much structure, they may be rigid and use harsh discipline; children don’t learn to think for themselves and they may either become passive or they might rebel. When parents give too little structure, their expectations and rules may be unclear and inconsistent. Children may feel confused; they don’t feel that they will be protected; and they don’t learn to be responsible.

Finding the Balance between Nurture and Structure

In addition to finding a place on each of these two scales that avoids the extremes of providing too much or too little caring or control, parents also have to find a balance between how and when to nurture their children and how and when to provide structure. Striking such a healthy balance is a challenge and contributes to making parenting an art rather than a science. While the times to be nurturing and the times to provide structure will vary based on the child, the circumstances, and the parents, it helps to take a step back and consciously decide which role will best help your child grow and learn – the nurture role or the structure role. In general, it is a mixture of both involvement and control that will lead to the best outcomes for your child.

Great Ideas:

During the upcoming weeks, notice and think about:

- In your everyday interactions with your children, which “role” do you find yourself in – the nurture role or the structure role?

- Which role are you most comfortable carrying out?

- Where do you find yourself on each of these scales?

- As you interact with your children, consciously decide if you need to be providing more love and attention or if you need to be providing more structure and guidance.

Part III The Three C’s of Discipline Overview

- Have you ever found yourself really struggling with disciplining your children?

- Do you find that you just aren’t as effective as you would like to be and that your attempts to discipline quickly spiral out of control with everyone getting angry at each other?

If so, you are not alone. Disciplining children is probably one of the least enjoyable aspects of parenting. Probably none of us signed on for this part of the parenting experience when we had our children. There is a general belief that disciplining is a negative thing, but if you were to look up the definition in the dictionary, you would probably find something that says: “discipline is training that corrects, molds, strengthens or perfects,” and it often has education listed as a synonym.

But how do you discipline or teach your children when you are feeling frustrated, angry, and unhappy?

The following are the 3 C’s of discipline. They represent the basic ways of responding to and confronting children that really help to lay the foundation for discipline in your home.

The first involves learning to remain Calm while in the throws of discipline. Although not always possible, you will be much more effective in getting your point across to your kids if you are not losing your temper and yelling and screaming at them. Learning to stay calm helps you to discipline with a clear head.

The second C involves Getting Clear about why you are disciplining your children in the first place. Look at your values and think about what is important to you and focus on those things. For example, if it is important that your children are polite and respectful, you can work with them on learning things like how to say please and thank you.

Learning to Be Clear also involves being specific when asking your children to do things. For example, asking them to “be nice” doesn’t really tell them how to behave. But asking them to “Sit up straight and use a fork while eating” is a much clearer message. The clearer you are, the more likely your children will listen to your requests and comply.

The 3rd and final C involves learning to be Confident about your job as a disciplinarian and about your right to be the executive in your home. You don’t have to be mean when you discipline your children and you have a right to be in-charge, especially when you are helping your children to become more responsible and respectful individuals.

It is important to remember that disciplining is a vital and necessary part of parenting.

To make your job a little easier, remember the 3 C’s.

- Learn to remain Calm and behave in a calm and neutral manner.

- Learn to get and be Clear about why you are disciplining and what you are communicating to your children.

- And be Confident in yourself as a parent who has the right and responsibility to provide discipline.

Part IV: Staying Calm

- Have you ever found yourself really losing it on your kids while trying to get them to do things around the house?

- Do you find your temperature rising the minute your kids start to fight or protest about your requests?

If so, then you and your family will benefit from learning how to stay calm. It is the first of our 3 C’s of effective discipline, and it enables you to set limits with your children in healthy and more productive ways.

Staying calm is probably one of the most difficult things to do when disciplining your children; yet it is one of the most important skills that you can learn.

Keep in mind, however, that it is not possible to stay calm all the time. In fact, anger is a normal human emotion that everyone experiences. It is important to know that venting your anger on your kids is not disciplining them and that intense anger can frighten children. There are ways to express your anger that are healthier and do not hurt your relationship with your youngsters. Learning to be calm is an important first step.

Being calm is both a skill you can learn and an attitude you consciously chose to adopt.

Even faking calm is more effective than disciplining while in the throws of anger.

There are a number of reasons why learning to stay calm is so important.

- First, it allows you to maintain control over your reactions and responses. You are less likely to say and do things you would later regret if you stay calm.

- Second, it helps you to stay focused on the issue at hand. Disciplining is not about being angry or raising your voice; it is about teaching and guiding your children.

- And third, calm invites calm. When you are calm, your children in turn are more likely to be calm, thus avoiding those endless cycles of yelling and screaming.

How can you learn to be calm when you are feeling so frustrated with your children? The following list of tips will help.

- Be reasonably soft spoken. Children sometimes listen better the lower your voice; even whispering can have a powerful impact.

- Speak slowly and clearly

- Use a firm voice

- Describe specific expectations and behaviors. “I expect you to hang up your coat when you come in the house.”

- Use appropriate eye contact – with young children, get down on their level.

- Become aware of your tone of voice and your body language. Pay attention to the words you use.

- Be unwilling to get into a debate or battle. Your kids can usually out-argue you. To help you stay calm, you can:

- Use shoulder shrugs and phrases like “That may be” and “I understand that….”

- Use a “broken record” technique, where you repeat the rule or request, such as “The rule is you have to finish homework before playing.”

- Refuse to be rushed – if your kids need an answer now, your answer will be “no”. If you have time to think about it, they may get a “yes.” Allow yourself time to get more information and to think about your response.

- Give reasons freely but not when emotions are high. When everyone is calm, you can give brief, respectful reasons for your decision or demand.

By remaining calm, you will find that you feel better as a disciplinarian in your home. You may find that some of the yelling and screaming will be happening less frequently.

Conclusion

Disciplining your children involves teaching and guiding them to become responsible and productive individuals, and it is a vital and necessary part of parenting. If you find that you are getting angry far too often with your kids, then chances are you are not disciplining effectively, but instead are venting your anger and frustration. Learning and practicing to stay calm will help you be a better parent and will help your children to become more responsible.

PART V Getting and Being Clear

This article will focus on the second of our 3 C’s of effective discipline – the skill of getting and being clear while you set limits with your children.

The following comments may sound familiar to you:

“Mom, why can’t I go to the mall with my friends?”

“You said to get ready for bed, I didn’t know that you wanted me to brush my teeth.”

“Can I just finish playing this game?”

On the surface, these comments may appear to be simple requests or statements. But as parents know, the real issues often lurk beneath the surface. Even straightforward requests can send you into a tailspin.

Let’s take a peak at what the parents who shared these comments were thinking:

“Mom, why can’t I go to the mall with my friends?”

PARENT IS THINKING: Well, I don’t know. Who are you going with? What age is appropriate for children to go to the mall by themselves? Is my answer the same if it is daytime or nighttime? Whose money will you spend? How do I feel about children going shopping as a leisure activity?

Or how about:

Can I just finish playing this game?

PARENT IS THINKING: Sure, I guess so. Tomorrow is not a school day. But wait, tomorrow you have soccer and then a friend’s birthday party and then we have a family dinner to attend. It’s going to be a pretty full day. You woke up late today and we had a miserable morning. Soccer doesn’t start until 11. Do I even know how long this game lasts?

Or what about:

“You said to get ready for bed; I didn’t know that you wanted me to brush my teeth.”

PARENT IS THINKING: Oh my goodness, do I have to spell out everything? Haven’t we followed the same routine for the past eight years?! Won’t you ever learn? Other parents don’t seem to have these problems. What am I doing wrong?

No wonder parents are exhausted.

The problems illustrated in these examples emphasize the important parenting skill of clarity, which includes two parts:

- Getting clear about what is important to you when it comes to raising your children

- Being clear so that your children understand what it is you are expecting of them.

Let’s examine the concept of getting clear a little closer. This step involves knowing what you value. Sometimes you are very sure about the things that are important to you. For example, you may value respect and are very clear that your children may not hit you or curse at you. But sometimes the lines are a bit blurry. Can your child yell at you? Call you names? What about slamming a door? Stamping their feet? What about leaving the room and not talking to you? Does your answer change if your child is two? What about if he is twelve? The response to each of these questions will not be the same for everyone. There is no one universal truth and you need to determine what is acceptable to you.

Additionally, even if you are very clear about what you value, sometimes these things can clash. Consider the following story:

A middle-school aged child asks to participate in a school fundraiser. On one hand, the mother is thrilled because she places a high value on charitable activities. On the other hand, she also values family time and wants the family to have a quiet evening at home together. It can be difficult to weigh these contrasting thoughts. To complicate the matter further, the father may have his own set of values that may support or further obscure the issue.

When trying to get clear, there are steps you can take to help:

- First, give yourself time. You can feel pressured to give an answer to a request right away. This expectation seems reasonable if you are looking at it on the surface as a straightforward question. “Can I have it?” The answer appears to be a simple “Yes” or “No.” Yet as we have just examined, the values that you may be debating can be far more complex. You can allow yourself time to weigh properly all of the issues so that you can come to a conclusion that leaves you feeling good. To your children you can say “I need time to think,” or “If you need an answer right away, that answer is “no.” Quickly they will realize that it is worth giving you time.

- Next, identify the underlying values that are being questioned. See if you can articulate what value you are struggling with.

By getting clear, you can avoid unproductive arguments. Let’s return to the first example of the child wanting to go shopping. The parent and child may spend a lot of time disagreeing about what is an appropriate age for children to go to the mall un-chaperoned, when the real issue for this parent is valuing the completion of work before play. The parent wants the child to help with chores around the house. Had these tasks been completed before the child requested the social plans, this parent may have consented.

Figuring out your values can take time, and you may not know why you are having trouble saying “yes” to your children until you find yourself grappling with the same issue repeatedly. As a pattern appears, you can determine when consenting to a request helps instill your values and when your acquiescing is in conflict with them.

- And finally, discuss your values with others who share parenting, childcare, and teaching responsibilities with you. For example, one parent may value a child receiving a “good” report card. Another may value a child’s love of learning. At times, these two goals are in sync. At times, they are at odds. By having an open discussion about the underlying issue, you can compromise. Perhaps you agree that loving to learn is more important and that it is ok for a child to get off track reading interesting material that is not pertinent to the test, as long as the child achieves a certain minimum grade.

Being Clear

Even once you take the time to become clear, you need to be sure that you are clear when you set limits or state your requests, positions, and values. Sometimes children just don’t know what you want. They are still learning and although it seems obvious to you that getting ready for bed includes brushing their teeth, this fact may not be apparent to your children.

When being clear, keep these guidelines in mind:

What specific behaviors are you requesting? For example, when you tell your child to clean up his room, you need to specify that “cleaning up your room” means: pulling up the covers, putting dirty clothes in the hamper, putting books on the shelves and so on. As children get older, you will be able to remind them with a broad “Clean up your room.”

- When does it need to happen? – Sometimes parents make an open ended statement, such as “Take out the trash.” You may not expect immediate compliance, but when an hour passes, you may feel your anger rising. Confronting your children may bring innocent replies of “I was just about to do it.” More effective is to make a request with a time component attached “Take out the trash before dinner.” Then you can both agree whether or not the action has been completed in a timely fashion.

- What qualifies as having completed a task? – Sometimes parents get frustrated because they feel that their children have given a job short shrift. Yes, they may have completed the task, but they have not done a quality job. Before you jump all over your kids, step back and make sure you have clearly stated your expectations. Do they know what an acceptable job is? For example, if they put away their laundry, do they need to neatly stack the clothes in their drawer or is just being out of sight okay with you? When you clearly state your expectations, then you will both know if a job has been completed satisfactorily.

Additionally, think about how you phrase your comments.

- Do not ask a question, unless you want an answer. If you want your child to stop watching TV because it is time to take a shower, do not ask, “Do you want to take shower now?” unless there really is a choice. Parents find themselves asking in hopes of gaining agreement from their children and avoid being the “mean” guy. Another way that parents undermine themselves is by adding an “okay” to an otherwise straightforward request. “Time to leave, ok?” Unless you are willing to stay longer, you are setting yourself up for a power struggle.

- Also, avoid using sarcasm. Children have difficulty evaluating sarcasm, and it can leave them feeling unsure of both your meaning and what they need to do. Take the child who is happily mixing all of the food on his plate into a large pile. Perhaps the parent responds with a sarcastic, “Oh, it certainly is a pleasure eating dinner with you.” The child is left to decide if the parent really is pleased with him – maybe a highly creative parent would be, or if the parent is asking him to stop. Rather than leaving the child to interpret your meaning, it is more effective to say, “Please stop mixing your food and eat your dinner.”

- Finally, avoid rhetorical questions. Like the “Okay” at the end of the request, rhetorical questions invite an answer, when there really isn’t a choice. For example, there is no appropriate response to the question, “Are you trying to drive me crazy?” It is far better to say, “Stop the yelling. Use indoor voices.”

Closing

As you learn the skills of getting and being clear, you may notice yourself questioning your values and stopping to listen to your words. At first, this process may feel time-consuming and artificial. With time, however, you will incorporate these skills into your everyday parenting and find that parenting becomes easier and more efficient. Moreover, you will discover that your relationship with your children becomes closer as you both are clear about what is important and what needs to occur.

Part VI – Being Confident

For many people, the image of being a parent prior to having children did not involve being a disciplinarian. Visions of loving your children, playing with them, spending time with them, and perhaps teaching them had readily come to mind. But as soon as children become toddlers, it is clear that in order to be a “good” parent, an additional stance is needed.

Learning to be a confident parent is one of the 3 C’s of discipline that lays the foundation for setting limits in a healthy and more productive way.

As a parent, being willing to assume the “in-charge” role which provides safety and structure for your children takes confidence. You have to believe that being assertive and setting limits is important for your children, as well as a necessary part of healthy parenting.

Confident parents take into account their own needs as well as their children’s and they work hard to balance these often conflicting requirements. They believe that their children have the capacity to cooperate and they are certain that their children will mature over time. They set limits in ways that are respectful and kind yet firm. With these attitudes, they do not dread or feel guilty about disciplining their children. Disciplining feels less like a burden.

Benefits of Being a Confident Parent

With the assurance that you are helping your children to mature and develop important character traits, disciplining won’t feel so distasteful and you can even feel good about the limits you set. This stance will help you to take a more relaxed and more unemotional approach so that you can avoid any confusion, ensuing power struggles, or possibilities of getting sidetracked by other issues. For example, if you are convinced that you have a right and a responsibility to set a bedtime for your children and that it is in their interests that you do so, you are less likely to be swayed by their nightly protests.

If you are a person who finds being assertive in other areas of your life difficult, there is also an interesting side benefit to becoming confident about disciplining your children. You can actually use that experience to increase your comfort level with being assertive in all areas of your life. As you do that, you provide a model for your children, thus increasing their confidence and self-esteem.

Your children also benefit directly by having parents who are willing to take a stand. By having standards that you hold your children to, by stating expectations clearly, and by holding your children accountable for their behavior, you will help them to gain character traits such as maturity, responsibility, trustworthiness and honesty. For example, if you establish a definite time that you want your children to be home by when they visit friends, a confident parent would confront them if they are late and perhaps impose a consequence. In this way, your children will learn to respect their commitments in the future by coming home on time.

When you don’t give in to their every wish, you are teaching your children to delay gratification, to consider the needs of others, to learn your values, and to tolerate a bit of frustration. If you refuse to buy the “in” game because you want your child to save his money to make the purchase, he will learn to work towards a goal and to appreciate the value of money and the things he has.

Attitudes of the Confident Parent

Adopting certain beliefs and attitudes about the job of parenting will naturally increase your confidence level. An in-charge parent knows the following:

- It is your right and responsibility to act as the executive in your home.

- You do not have to be mean and uncaring to be assertive and confident.

- You can promote your children’s self-esteem and maintain a healthy relationship with your children, while you are being firm and assertive.

- You have confidence in your judgment as the adult, knowing you have wisdom based on life experience and knowledge of the needs of your children.

- You are a benevolent dictator when children are young and immature. Gradually, as your children grow and their judgment improves, you hand over decision making, responsibilities, freedoms and privileges to them.

- It is alright for your children to momentarily feel angry, rebellious, or upset by you. They can still obey and behave appropriately even if they don’t like your rules and decisions.

- You can be flexible, change your mind, and compromise from a position of strength – the decision to do so is yours.

- Your job is not to always make sure your children are happy.

When your relationship with your children is trusting, loving and supportive, children will feel protected by the structure of discipline, even if they don’t acknowledge it to you. Having this kind of positive relationship is the key to healthy discipline and is what will make it more likely that your children will follow your guidance and accept your rules.

Specific Techniques of a Confident Parent

As a confident parent, you are willing to:

- Deny your children’s requests when they are unreasonable:

For example, you may refuse to buy an expensive, designer pair of jeans because you don’t want to spend that much money or because doing so is in conflict with your values. - Demand that your children act in responsible ways to meet reasonable expectations:

You may insist that your children treat everyone in your home with respect. They can express their feelings, but they may not call names or curse.

You may require that they stop teasing the family pet, while you show them how to play carefully with Fido. - Delegate certain tasks to your children that are appropriate for their age and development and that help them to gain a sense of responsibility.

You may assign age-appropriate chores to your children, and you follow-up to make sure they are completed in a satisfactory and timely fashion.

For many parents, adopting these attitudes does not come easily or naturally. You may be more comfortable nurturing and enjoying your children than disciplining them. You may fear that assuming the “structure” role will harm the relationship you have with your children, making them resentful or that it may even harm your children by stamping out their creativity. In reality, the opposite is more likely to happen: children will learn that you are there to protect and to guide them, even if they are temporarily unhappy with the decisions you make.

Becoming confident may take some “self-talk” and conscious effort to overcome any concerns you may have about saying “no” to your children’s requests. By realizing that this is part of the parenting job, you can become more confident. In the long run, your children’s self-esteem and your relationship with them will be stronger for it.

____________________________________________________________

For more information about fostering responsibility in children, check out the following books. Purchasing from Amazon.com through our website supports the work we do to help parents do the best job they can to raise their children.

<For a list of all our recommended parenting books, click here.

If you found this article helpful, click here to make a donation to The Center for Parenting Education. Your support will enable us to continue to provide quality information free of charge.

ut I get so frustrated.”

ut I get so frustrated.” in but I don’t have the time or energy to outlast them. Sometimes I feel like I am too weak and am a pushover.”

in but I don’t have the time or energy to outlast them. Sometimes I feel like I am too weak and am a pushover.”