Who is on your Parenting Team?

You may wonder how you can develop an effective partnership with the people who are involved with you in raising and caring for your children. These can include:

- your co-parent,

- grandparents,

- caretakers,

- teachers,

- coaches,

- other involved adults.

Not only is this support important for the healthy development of your children, but it also makes the job of parenting less frustrating and more rewarding.

What is a Parenting Team?

Team parenting is a mutual commitment between people involved in the care of a child to:

-

share basic philosophical positions about parenting;

-

support one another and appreciate each other’s beliefs, needs, strengths, and efforts;

-

be flexible;

-

give feedback and constructive criticism to one another in a healthy and supportive way – you do not need to agree with your co-parent in their approach or ideas, but as parenting partners, you do need to listen to each other’s point of view;

-

plan together how to deal with major issues or persistent problems – discuss rules, expectations, and discipline issues.

Obstacles to Creating a Parenting Partnership

In an ideal world, the team parenting approach outlined above is what should happen; but we don’t always live in an ideal world.

There are three main areas that can pose roadblocks to your efforts to team parent:

- The Adults;

- Family of Origin Issues;

- The Children.

What Adults do to Make Team Parenting Difficult

Relationship Problems

Sometimes other issues between co-parents play out through the children. Parents may use discussions about children as a means of starting fights with each other, without ever resolving the child-rearing problem.

For example:

- one parent may blame the other for a poor parenting choice in order to add one more piece of evidence that the partner is incompetent or wrong;

- one person may not stand up for his opinion about how to handle a situation because he is comfortable in the role of martyr and wants to maintain his position as the victim in the relationship;

- simmering anger between partners can be played out through constant undermining and criticism of the other’s parenting decisions.

On the other hand, parents may be reluctant to discuss parenting concerns for fear that such talks could lead to conflict between the adults.

Abdicating Parental Responsibilities

Sometimes parents allow others to make the major parenting decisions about their children. This might be due to insecurity, uncertainty, lack of time, or the strong personalities of the other people involved.

For example, a young mother may be reluctant to tell the regular babysitter how she wants her toddler put to bed. The babysitter is an older woman with grown children, who has very strong ideas about how things should be done with children. The mother goes along with the babysitter’s rules even when she feels uncomfortable about them.

Rigid Role Divisions

One parent may always be the disciplinarian and the other always the nurturer. You can hear the constant nurturer saying “Just wait until your (Father /Mother) comes home” when a child needs to be disciplined, rather than dealing with the situation directly at the time.

For example, a mother says to her ten-year-old son who refuses to turn off the TV and clean up his toys, “Just wait until your father gets home. You will be in big trouble. He is going to take care of this once and for all.”

Acting Impulsively

One caregiver may set consequences when he or she won’t be around to follow through on them and make sure the child complies. This can cause a problem for the “on-duty” parent who is then put in the position of being the enforcer.

For example, a grandmother caring for a four-year-old grandson while her daughter-in-law works three days a week tells him that he will not be allowed to watch television when he goes home that night because he spilled his milk and refused to help her clean it up. It is the daughter-in-law who is left to follow through on the consequence even though she was not there when the problem occurred.

Another example would be a mother letting a three-year- old take an extra long nap when it will be the father who will be home alone with the child at night.

Undermining your Co-Parent

Sometimes a parent contradicts the other parent by interfering in front of the child with a situation the first parent is already handling, instead of waiting for a private moment to discuss differences in parenting.

For example, a father is disciplining his eight-year-old daughter for talking back to him. His wife interrupts the father-daughter exchange to chastise the father, saying that she does not think that their child was so disrespectful. Furthermore, the mom takes the daughter’s side, telling them that the father was at fault because he had embarrassed the daughter in front of her friends.

Differing Values

Parents may value different traits in their children and therefore have different goals, reinforce different behaviors, want different rules in place, and send contradictory messages.

For example, a mother and father argue because the mom wants their twelve-year-old daughter to take Saturday afternoon tennis lessons so she can learn skills, develop interests, and be with other children while the dad thinks his daughter needs to learn to entertain herself and spend time with the family.

How Your Family of Origin Interferes with Effective Team Parenting

Most people parent their children the way they were parented. This is due to a sense of loyalty to their parents, not knowing how to do things differently, or feeling good about how they were raised – that it was fairly effective and had a good result in terms of how they developed.

But if parents came from homes with very different parenting styles, this can lead to conflict and misunderstandings.

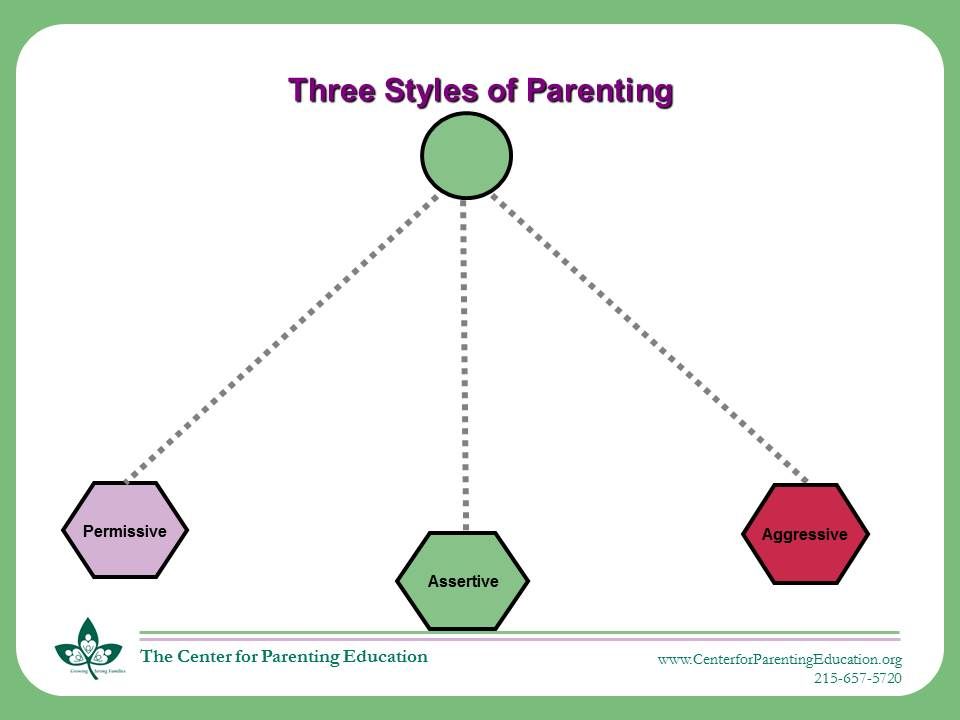

The Three Main Parenting Styles

There are basically three different parenting styles with two being at opposite ends of a discipline pendulum arc and one being in the middle between the two extremes.

The Permissive Style is at one extreme of the continuum. This parent does not set limits, say no, discipline or hold children accountable. In this family, the children rule the roost.

The Aggressive Style is on the other extreme end of the continuum. In this family, children’s needs and feelings are not considered. Rigid compliance from children is demanded, and children are to be seen and not heard.

The Assertive Style is the middle style, between the two extremes. Parents who use this style consider the needs and feelings of both the parent and the child. The parent is:

- respectful,

- teaches the child how to be respectful

- expects to be treated with respect

- set firm yet flexible limits

- stay calm

- are clear in communicating their rules and expectations

- are confident in their need to impose limits and do so in a caring way.

An Example of the Three Styles of Parenting

Here is how each of these three different types of parents might respond to the same situation: Ten-year-old Ari leaves his games, books, and clothes all over the family room even after being told numerous times to pick up after himself.

Permissive:

“Oh, Honey, I see your stuff is still left out. I guess you were too busy to clean up. I’ll do it for you so you can find everything next time you want to play with them.”

Aggressive:

“I’m sick and tired of seeing your things all over the room. Why are you such an irresponsible slob? That’s it for you – you are grounded for a week and I’m throwing out all your things.”

Assertive:

“Ari, I see your games are still not put away as I asked you to do. It is really bothering me that I can’t count on you to take care of your things and I can’t stand seeing the family room be such a mess. We need to come up with a plan for you to put your things away. Until we come to an agreement, there are no electronics for you.”

How Parenting Styles Impact your Parenting Team

It may be loyalty to the parenting style used in your family of origin that leads you to be the consistent nurturer or an overly strict disciplinarian.

Often, you and your co-parent may not start out too far apart from one another, but as time goes on, your roles solidify. Each of you goes further and further to the extreme in order to compensate for what you each see as inadequacies in how your partner handles situations.

You may not have had a role model for an effective team approach if your parents did not work together in a supportive partnership in raising you.

You may live in a family arrangement different from the one in which you grew up, and for which you have no experience and no blueprint to use to build healthy family dynamics. Some of these other family configurations can include:

- grandparents raising children,

- single parents,

- parents living with their parents,

- two working parents,

- or divorced families in which children need to adjust to the homes of each parent.

The Impact Children Have on Effective Team Parenting

Birth Order of the Child

Sometimes you may identify more with a child who is in the same birth order as you were in your family of origin. You may be more sympathetic to and understanding of that child’s perspectives.

For example, a first-born father may not want to burden his oldest child with too many chores and rules as he remembers feeling he had too many responsibilities on him when he was growing up, but a youngest co-parent may feel that the oldest child should babysit and spend time with the younger sibling as she may have wished her older sibling had done when she was growing up.

Temperament of the child and the parents

You may be able to relate better to children with similar temperaments, or conversely you may be more negative toward a child who has traits that you do not like in yourself.

For example, a very intense parent may really enjoy and identify with her child’s drama and passion, or she may dislike seeing that quality in her child, recalling how difficult it was growing up with the label of “drama queen.” The other parent may react entirely differently and have different responses to this child.

Children playing one parent/caregiver against the other

Children are experts at dividing and conquering, sensing areas of disagreement and using them to get around the rules. If you are not careful, it can lead to frustration and anger as you blame each other for not being supportive, holding to agreements, or respecting each other’s wishes.

There are many challenges that you must overcome to create a positive and effective team approach to raising children. Being aware of and recognizing these obstacles if they exist in your home can help you to avoid them.

Guidelines for Effective Team Parenting

Once you become aware of what factors may be getting in the way of creating an effect partnership with your co-parent, there are many skills and attitudes you can learn and adopt that will help you successfully get “on the same page” with the people who are involved in caring for and raising your children.

General Tips

-

Set aside a regular time to discuss what has been going on and to plan strategies for the upcoming week.

-

If one of you wants to try a new approach, ask your co-parent for support or, at a minimum, non-interference.

-

Avoid evading responsibility when a problem arises. Deal with issues as they occur.

-

Don’t interfere with a situation the other person is handling.

-

After problems have been solved, allow time to talk about the interactions and to give suggestions, praise, support, or constructive criticism.

-

Resolve differences of opinion in private, not in front of your children.

When Parenting Partners Disagree

If you can’t agree on an issue, one of you may need to back down temporarily or agree to disagree. Remember that you don’t have to be see eye-to-eye on everything. Each of you can have certain rules which are unique for your relationship with your children; there can be “Mommy’s rules” and “Daddy’s rules.”

However, these differences should be on the less important issues. In addition, you can go along with each other on some issues in exchange for support on others.

For example, you may want your middle-schooler to be able to go to his friend’s house on a Friday night; your husband may want him to spend more time at home. In exchange for letting your son go as you would like, you agree to back your husband on his request that your son help with raking leaves on Sunday.

When Children Try to Play Parents against Each Other

If your child seeks your support against his other parent, you can validate your child’s reactions, feelings, and perceptions. Encourage your child to work out the conflict directly with his other parent; you can offer to help him clarify his thoughts and present his feelings. While doing so, remain objective and do not take sides.

However, if you are concerned that your child is being harmed physically or emotionally, intervention may be called for, either in discussions with your spouse or co-parent or with outside resources.

Specific Team Communication Techniques

-

Stick to the issue, don’t get side-tracked. Don’t bring up other complaints. Stay in the now and discuss one issue at a time.

-

If your partner attacks, blames, or is disrespectful, ask him or her to speak more respectfully. You can refuse to continue a conversation in which you are not being treated with respect.

-

Use Active Listening. This is an important skill, probably the most important communication skill you can learn.

It is a way of listening that lets the speaker know that you understand what he is saying, accept his perspective, and are not judging him. It does not mean that you necessarily agree with the person but that you are available to hear his thoughts and feelings.

Using Active Listening often reduces defensiveness and goes a long way toward creating a cooperative atmosphere.

“I hear that you think I need to be more firm with Ashley when she does not do her chores on time.”

-

Use I-Messages when you want to express how you feel about the situation. It is a way to communicate your thoughts and feelings without blaming or attacking the other person. This skill involves remaining calm, clear, and confident. Be assertive, not aggressive.

“I am concerned that your punishment was more severe than it had to be to teach Sean to call us when he is not coming home right after school.”

-

Choose with broad approaches in mind. Don’t challenge every argument that is presented and don’t argue over details. Instead of mentioning every time your spouse has let your child “off the hook” this past week, stay with the big picture and later you can give specific examples.

“I’ve noticed that you haven’t been enforcing our house rules or imposing consequences when Nathan doesn’t do what you ask him to. Let’s talk about it.”

-

Accept responsibility for your parenting choices. Don’t make excuses for your behavior.

Instead of saying: “It wasn’t my fault” or “I was so busy,” or “I don’t have eyes in the back of my head, you know.”

You can say: “I might not have been paying as much attention as you think I should have been,” or “You don’t think I was paying enough attention.”

-

Accept that you and your partner may have different perspectives on some issues. Don’t take it as a personal affront, as long as the communication is respectful. You both may have valid, just different, perspectives. The goal is to come together and decide how you want to raise your children.

-

Focus on solutions, rather than finding someone to blame. Appreciate that there is some legitimate reason for almost every behavior.

Instead of saying: “It is your fault that Sam won’t cooperate now.”

You can say: “This is not about someone being at fault. The question we need to address is how we are going to handle it.”

-

Be assertive, not aggressive.

Instead of saying: “If you don’t talk to me about this now, I’m doing it my way, and that is that.”

You can say: “I understand that you feel strongly about this. I do too. We need to discuss this in order to work it out.”

-

Avoid lecturing. To decrease defensiveness in your partner, stay calm and objective and communicate your reactions in a descriptive, non-judgmental way.

Instead of saying: “You always over-react to things.”

You can say: “When Charlie didn’t clear the table, you seemed to get very upset and angry.”

-

It is important to talk with your partner directly, not through your children; avoid using them as a middleman. This is good modeling for your children; they will learn to be direct in their communications with people and they will learn the fine arts of negotiation and compromise.

It will help reduce opportunities for your children to manipulate you by playing one of you against the other, and will eliminate their need to take on inappropriate responsibility as a mediator.

-

When you receive a negative general statement, ask for more clarification and specifics.

If your partner says: “You don’t spend enough time with the children.”

You can ask: “What do I do that makes you think that?” or “How long have you noticed this?”

Team Parent Conversation Starters

The following ideas can be used as a starting point for a general conversation with your partner about intentionally and deliberately creating a partnership as you raise your children.

-

Explore each of your families of origin, how each of you were raised, and how that effects your current parenting.

-

Describe what you think each of you does well in parenting and areas where each of you can grow.

-

Talk about how you each can support one another to do the best job you can in raising your children.

-

Discuss together the traits you each value in your children, talking about differences as well as traits you agree on. Awareness of this can help you get on the same page with your partner about your goals for your children. Following is a list of traits that you and your co-parent can consider – how important to each of you is it that your children exhibit them?

| Active | Helpful to others |

| Aggressive | Honest |

| Appreciative | Humble, modest |

| Assertive, speaks up for self | Independent, self-reliant |

| Athletic | Intelligent, intellectual |

| Attractive | Kind |

| Brave | Loyal |

| Caring | Obedient |

| Cheerful | Passive, not aggressive |

| Clean, neat | Patient |

| Confident | Peaceful |

| Considerate | Persistent |

| Coordinated | Polite, well, mannered |

| Creative | Popular with peers |

| Curious | Religious |

| Determined | Respectful |

| Directed | Responsible |

| Enthusiastic | Self-controlled, self-disciplined |

| Flexible | Sensitive to others’ feelings |

| Focused | Social |

| Friendly | Spiritual |

| Frugal | Steadfast |

| Generous | Tactful |

| Gentle | Tolerant |

| Joyful | Trustworthy |

As you discuss all these issues, you can practice the healthy team communication guidelines mentioned above.

____________________________________________________________

For more information about discipline check out the following books. Purchasing books from our website through Amazon.com supports the work we do to help parents do the best job they can to raise their children.

<recommended books about discipline

<all our recommended parenting books

___________________________________________________________

<return to top of page